The Toccata and Fugue in D minor is a haunting organ work that can sound as if the organist is playing the entire building. It is easy to imagine how overwhelming it would be to hear this music in a vast cathedral, or even in a centuries-old mansion perched on a lonely hill. It is remarkable that a single instrument – albeit a very large one – can produce such a monumental sound, one that seems to vibrate through the body and overwhelm the space in which it is played.

As you will read below, there is still much debate surrounding this work, including questions about its authorship and original purpose. What is certain is that a piece written over three hundred years ago can still sound strikingly dynamic, forceful, and immense. One can only imagine the reaction of its first listeners when this music was heard for the first time.

The following was abridged from the Wikipedia article at the end of this post:

The Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565a is a composition for organ from the Baroque period. According to the oldest sources it was written by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach. It is one of the most widely recognisable works in the organ repertoire. Although the date of its origin is unknown, scholars have suggested between 1704 and the 1740s (if by Bach).

Little was known about its early existence until the piece was discovered in an undated manuscript produced by Johannes Ringk. It was first published in 1833 during the early Bach Revival period through the efforts of composer Felix Mendelssohn, who also performed the piece in 1840. It was not until the 20th century that its popularity rose above that of other organ compositions by Bach, as exemplified by its inclusion in Walt Disney’s 1940 animated film Fantasia that featured Leopold Stokowski’s orchestral transcription from 1927.

The piece has been subject to a wide, and often conflicting, variety of analyses. It is often described as a type of program music depicting a storm, while its depiction in Fantasia is suggestive of non-representational or absolute music (not about anything).

Scholars such as Peter Williams and Rolf Dietrich Claus argued against its authenticity, while Christoph Wolff defended the attribution to Bach. Other commentators have either ignored the doubts over its authenticity or considered the attribution issue undecided.

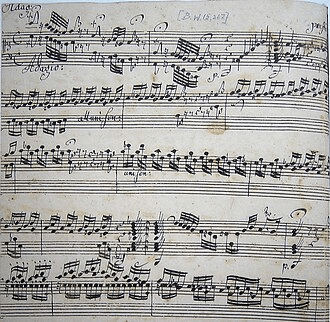

According to Dietrich Kilian, who edited BWV 565 for the New Bach Edition, Ringk made his copy of the Toccata and Fugue between 1730 and 1740. At the time Ringk was a student of Bach’s former student Johann Peter Kellner at Gräfenroda, and probably faithfully copied what his teacher put before him. There are some errors in the score such as note values not adding up to fill a measure correctly. Such defects show a carelessness deemed typical of Kellner, who left over 60 copies of works by Bach.

References:

1. Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 – Wikipedia

I love Bach. I listen to Bach almost everyday & of course I played a lot of Bach growing up & I still do ~ I have Bach Inventions for the piano ~ very difficult! But fun 🙂