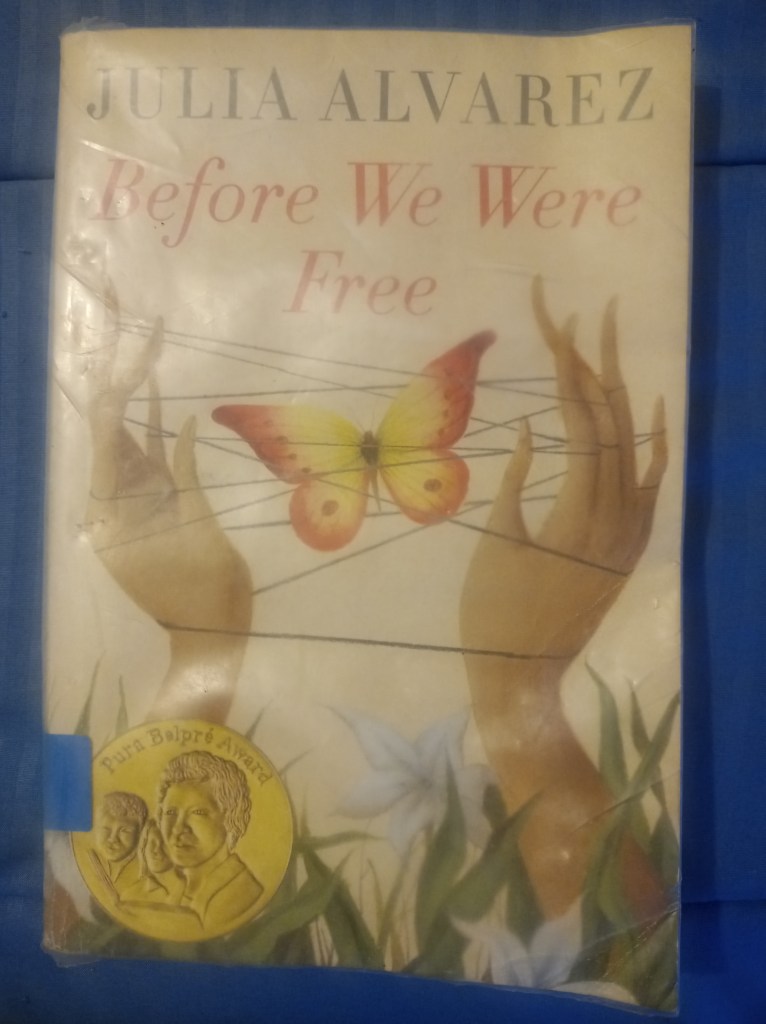

My Wednesday literature segment returns, featuring an excerpt from Before We Were Free by Julia Alvarez, which I finished reading yesterday. If you enjoy dabbling in books, feel free to join me on Goodreads [here]. My reading has been slow of late, but I am hoping to make amends.

Before We Were Free tells the story of twelve-year-old Anita de la Torre, living in the Dominican Republic in 1960. Although Anita is a fictional character, the author draws on her own childhood experiences of living under the authoritarian rule of dictator Rafael Trujillo.

It was a tumultuous time in the country’s history. The Dominican Republic had endured more than 30 years of dictatorship, and this first-person narrative, told through Anita’s eyes, explores the final violent and bloody year of the regime and its impact on one family. Anita’s family is partly in hiding because of their involvement in the underground resistance. The title also echoes Alvarez’s earlier work about the Mirabal sisters, known as Las Mariposas (The Butterflies), who became powerful symbols of resistance.

In real life, Julia Alvarez (image inset) and her family fled the Dominican Republic for the United States in 1960 after her father’s involvement in a plot against Trujillo was uncovered. This novel imagines the lives of those who stayed behind, fighting for freedom until Trujillo was assassinated in May 1961. Alvarez based parts of the story on testimonies from family members and friends who lived through that final year, one of the bloodiest in the regime’s history.

This short historical novel is written for young adults, and I did wonder whether I would find the subject matter engaging. The book deals with Anita coming of age – even worrying about her first period – while her family faces persecution and raids by the regime’s secret police. As a parent of a ten-year-old daughter approaching puberty, I felt there might be something personal to learn here as well.

The following contains spoilers:

I found the early chapters a little slow. Without meaning to sound condescending, adjusting to the plain and sometimes naive voice of a twelve-year-old narrator took some time, as it is not the perspective I usually read. But once the tension builds and the regime tightens its grip on this Dominican family – almost like prisoners in their own compound – the story becomes gripping. Everything is seen through Anita’s innocent eyes. She is still learning about her place in the world, while trying to understand the danger surrounding her family.

The family must remain vigilant. They often communicate in coded language because of constant surveillance, and there are even spies within their own compound. It is frustrating and unnerving as a reader, and it must be agonising for Anita, who simply does not know the full truth. Our understanding is limited to what she sees and hears. You witness how her innocence is gradually shaped by fear and by the disturbing acts of cruelty she becomes aware of.

The following extract comes from the final stage of the novel, when Anita and her mother are rescued from their hideout and taken to New York to rejoin other family members. They leave behind Anita’s father and uncle, who remain imprisoned. After Trujillo’s assassination, his son Ramfis Trujillo briefly took control and carried out reprisals. The author uses the word “ajusticiamiento,” meaning “bringing to justice,” to describe Trujillo’s killing. Anita and her family hold on to the hope that they will one day return to the Dominican Republic and reclaim the lives that were taken from them.

So without further ado, here is a brief passage that finds Anita adjusting to her new life in New York, where she begins learning English at a Catholic school. It contains some of my favourite prose in the entire book:

Mami goes to a nearby Catholic school and asks the principal if we can sit on any class till we get back home. The principal is a nun with a bonnet like a baby doll, except it’s black. She is a Sister of Charity, and may be that is why she is so kind and says yes, she will put us wherever there is a spot.

The next day, I don’t think she is so kind. I’m sitting at a small desk in the second grade, the only elementary classroom that had extra space. The teacher, Sister Mary Joseph, has a sweet face with pale whiskers and watery blue eyes as if she is always in tears. Her breath is musty, like an old suitcase that hasn’t been opened in years.

“Annie is a very special student,” she tells the class, “a refugee from a dictatorship.” When she says this, I stare down at the wooden floor and try not to cry.

“She came here with her family in order to be free,” Sister Mary Joseph is explaining. But my family is not all here, I feel like saying. And how can I be free when my mind is all worried about Papi and my whole self is so sad, I can barely get up some mornings?

“Would you like to tell the class a little something about the Dominican Republic?” the old nun prompts me.

Where do I begin telling strangers about a place whose smell is on my skin and whose memory is always in my head? To them, it’s just a geography lesson; to me, it’s home. Besides, talking about my country would would make me too sad right now. I stand in front of this roomful of staring little kids, not saying a single word. At the very least I should show them that I can speak their language, so they don’t think I’m a complete moron who is almost thirteen and still in the second grade.

“Thank you,” I murmur “for letting me into your country.”

Sister Mary Joseph gives me an assignment to do on my own. I am to write a composition about what I remember from my native country.

“Maybe it’ll be easier to write down memories rather than just think on your feet,” she suggests. She shows me how I’m supposed to make a little cross at the top of each page, and then print the initials J.M.J., dedicating my work to Jesus, Mary and Joseph.

Below, on the first line, I am to put my own name, which she writes out as Annie Torres, and the date, October 4, 1961.

I bend to my work, make my little cross on top of a clean page, dedicating my composition to J.M.J. But then I add M.T. & A.T., Mundo and Antonio de la Torre.

“What’s that?” Sister Mary Joseph says, peering over my shoulder.

“My father and my uncle.” I point to each set of initials.

She is about to protest, but then her watery blue eyes get even more watery. “I am so sorry” she whispers-as if Papi and Tío Toni are dead!

“I will be seeing them soon,” I explain.

“Of course you will, dear,” Sister Mary Joseph says, nodding. Today, her breath smells like the sachets my grandmother sticks in her underwear drawer.

Leave a comment